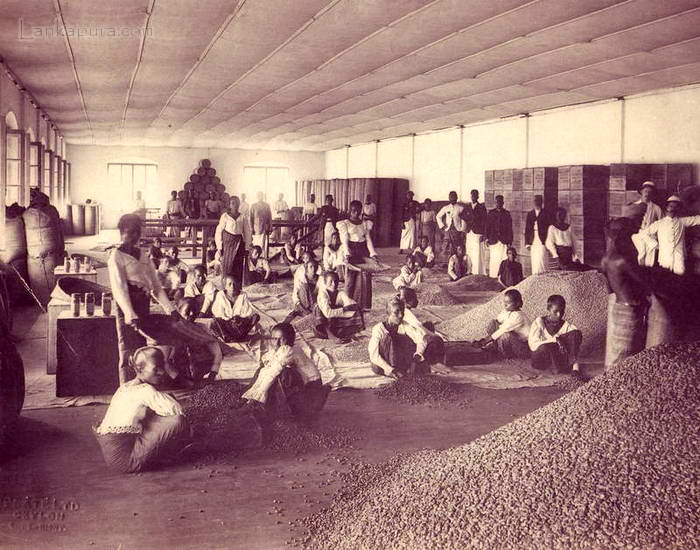

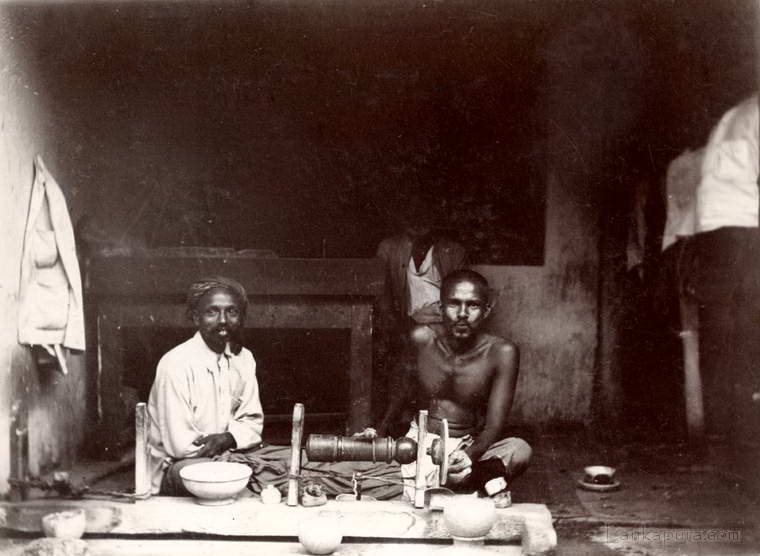

Photography/Publisher: Plate Ltd, Colombo.

Coffee Production In The British Empire 1800s

THE chief coffee-producing countries in the Empire are India, Jamaica,

British Central Africa, and Ceylon.

In a work published some years ago on the products of this most beautiful tropical island, it is said that when in 1836 the duty on coffee in England was reduced to sixpence per pound, a great impulse was given to coffee planting. If such was the case, and it certainly was, then how great ought the production be to-day when the duty is only three halfpence. Yet though only a quarter of a century ago coffee was the principal product of the colony, and the value of the annual crop exported exceeded 3,000,000, now it is only about £25,000, whilst tea occupies the premier position.

From very early times it is recorded that coffee grew wild in many parts of the island, but during the decade commencing with 1836 there was what can be only described as a rush for lands said to be only paralleled by the movement towards the gold mines in California and Australia. The mania so acted upon all classes that we are told even the governor, council, military, judges, civil servants, and clergy all swarmed to the hills to purchase the Crown lands which the authorities were only too ready to sell and did so to the extent of about 40,000 acres per annum. Officers of the East India Company sent their savings to invest in what was to be an El Dorado, then the crash came, hastened by two causes ; first, the financial panic through which England passed in 1845, and, secondly, the withdrawal of the protective duty—for this happened in the days of protection to which we are asked once more to return a duty being charged on the product of Java, Brazil, and other coffee-growing countries in excess of that levied upon the British-grown product. Still the crisis had some compensations, for it led to a healthier condition of planting, economics were introduced into the management of the estates, and scientific principles were established instead of the many different schemes which individual planters without any real knowledge endeavoured to carry out. While there are still a few left in the trade who can remember when ” Plantation ” and ” Native ” Ceylon were the two principal kinds used by the grocers throughout the kingdom ; today Ceylon coffee is. hardly known as an article of commerce and certainly the greater number of grocers have never sold a pound of this once favourite description. The term native has always been, as applied to Ceylon, somewhat of a misnomer, for though coffee is reported to have grown wild there, it is more than likely that it had been brought by Arabian traders. In later years, the term was applied to that grown on more hardy trees, which were planted around a garden or plantation, and did not receive the same care and attention as the product of these plantations did, while the crops grown on them were looked upon and treated as part of the wages of the natives, or coolies, who were employed on the estate. The final blow to coffee culture in Ceylon came with the development of the leaf disease, which is here described, and though for a time Liberian coffee was introduced which it was hoped would resist the ravages of this pest, even that has had to give way to the more profitable tea and rubber, for both of which the island has become noted. Whether the’ high prices obtained, for the small quantity grown, will induce further cultivation is open to question, for though the’ quality of the product stands quite alone, and will always ensure a ready sale, yet with an increased production there would naturally be a corresponding reduction in price.

Coffee Leaf Disease. The Ceylon coffee industry was ruined owing to the attacks of a minute fungus, known as Hemileia vastatrix, very similar to the rust of wheat. The disease was first noticed in 1869, when it was already fairly well distributed throughout the island and had probably been in existence for some time. The characteristic outward sign of the disease is the formation of a number of yellow spots on the surface of the leaves. Owing to the fungus using up the plant’s food, the coffee plant is weakened, its leaves fall long before they would if not attacked, only a small proportion of the. flowers develop sound fruits, and accordingly a very poor crop is the result, whilst the whole plant is weakened and may finally be killed. The disease was very carefully investigated by the late Professor H. Marshall Ward in 1880-81, but no curative measures could be discovered. The greatest assistance was rendered by the Botanic Garden, and the Ceylon planters displayed wonderful energy in meeting the disaster. Within a year or so after the disease was noticed in Ceylon it appeared in Southern India, and rapidly spread to other countries also, the spores probably having been introduced in various ways; practically all the coffee-growing regions of the Old World were affected. The disease is so dreaded that other countries took, and still take, every possible precaution to guard against its introduction.

Source: oldandsold.com >>

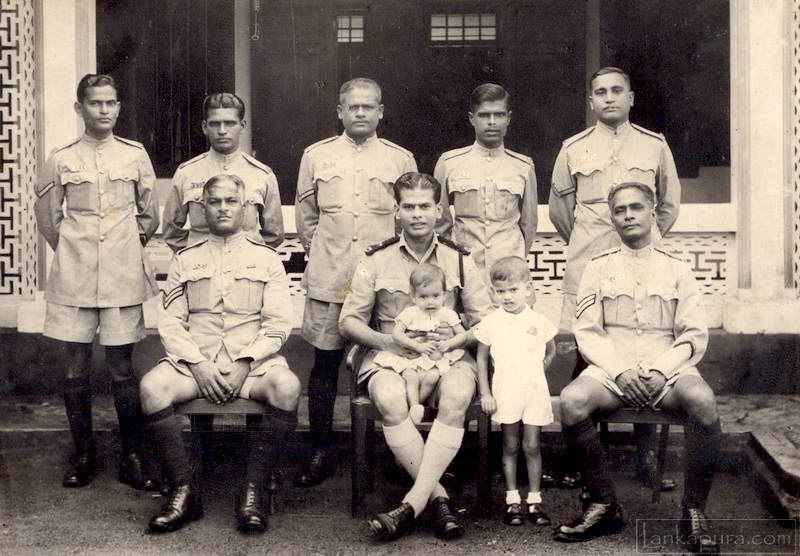

Hello. I am a trustee at Dimbola Museum & Galleries, Isle of Wight, UK and am writing a project on Julia Margaret Cameron (Victorian pioneer portrait photographer) born in Calcutta and died in Sri Lanka where husband Charles Cameron owned coffee plantations – in fact – Dimbola named after one of them. I came across this image and would like to use it. Of course – credited – if you can tell me who to credit. Do I have your permission please? thanks so much, best wishes, Jane (It WILL appear on a small film online – but don’t think it will have a wide audience – very niche! It is for educational purposes – I am not making any money out of it. I also hope to show the little film out in Calcutta, where Julia – although born there -is very little known. thanks!